- A

- A

- A

- ABC

- ABC

- ABC

- А

- А

- А

- А

- А

- HSE University

- Faculties

- Faculty of Humanities

- School of History

- News

- Research & Expertise

- Lost in Recalculation: How to Estimate the Scale of the Soviet Economy and Its Rate of Growth

105066 Moscow, Staraya Basmannaya 21/4, building 3

Phone: +7 (495) 772 95 90 *22858

The HSE School of History was established in 2015 on the basis of the HSE faculty of history. The School's staff brings together leading scientists in various fields of historical knowledge who are widely known and respected in Russia and the international academic community. The School’s instructors are leading historians are authors of numerous books and articles, regular participants in major international scientific forums and research projects, and are also known as popularizers of historical knowledge. The HSE School of History actively cooperates with leading foreign universities and research centers, and organizes international scientific conferences, symposia, and colloquiums.

Strasbourg: Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 2023.

Misiak M., Butovskaya M., Sorokowski P.

Food Quality and Preference. 2024. Vol. 114.

In bk.: Picturing Russian Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024. Ch. 6. P. 66-73.

Kolesnik A., Rusanov A.

Working Papers of Humanities. WP. Издательский дом НИУ ВШЭ, 2021. No. 205.

Lost in Recalculation: How to Estimate the Scale of the Soviet Economy and Its Rate of Growth

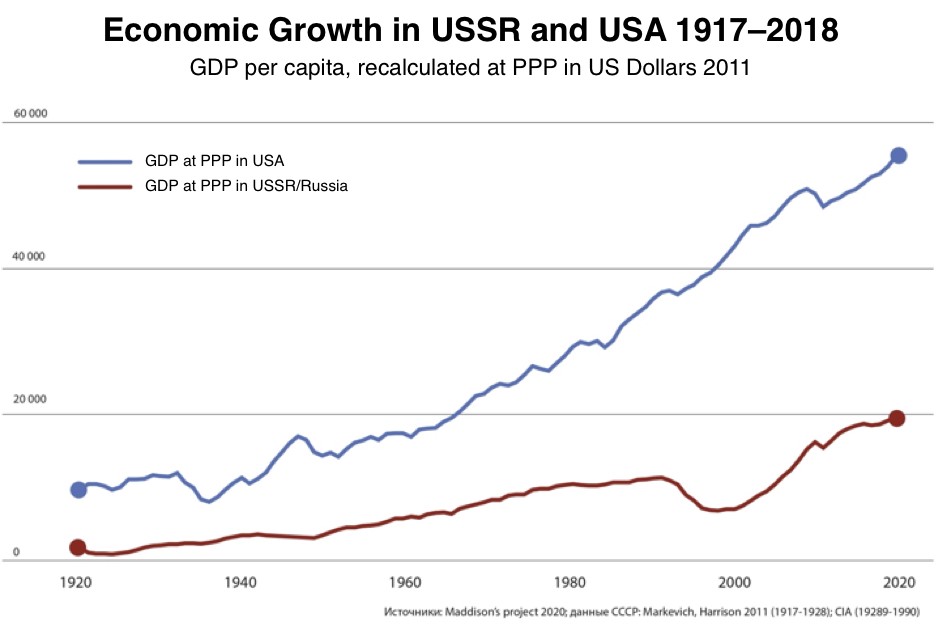

Researchers trying to compare economic data of the USSR and capitalist countries face questions of the comprehensiveness, accessibility, and reliability of data on Soviet economic production and growth. At an online seminar hosted by the HSE University International Centre for the History and Sociology of World War II and its Consequences, Assistant Professor Ilya Voskoboynikov (Faculty of Economic Sciences, HSE University) presented an overview of available approaches to studying the absolute size of the Soviet economy and its growth rates.

Soviet economic growth and production rates remain an area of focus for contemporary researchers, insofar as they shed light on reasons behind for the deceleration of the Soviet national economy and the role economic factors played in the Soviet Union’s collapse. To study these problems and compare the economic indicators of the USSR and capitalist countries, sets of comparable data are needed.

World statistics now predominantly use the System of National Accounts (SNA), but in the case of the USSR, due to the lack of market prices and the difficulty of calculating defence expenditures, it does not always work. The official statistics of planned economies are based on the balance of national economy (BNE) and the concept of national product, which differ from the now familiar gross domestic product (GDP).

However, a significant part of government and defence services dropped out of the BNE, which, together with price regulation, creates unavoidable obstacles to measuring the GDP of planned economies, notes Ilya Voskoboynikov. Consequently, a comparison of the USSR’s national income and the United States’ GDP and their growth rates does not provide an accurate picture.

A serious problem is that comparing prescriptive prices with free market prices, together with the lack of data on real inflation, will yield incorrect results. To calculate prices, it is possible to use an adjusted factor value, taking into account indicators that were not taken into account in the USSR, such as profits and land rents, but these calculations contain certain assumptions.

If one studies a single product that can be measured in tons and rubles, then one looks at the physical volume of production. However, the economy consists of many products and services and the problem of index arises: how to measure everything using a single number and how to figure out the weight of each industry. Many indexes can be created, but the choice of base year and base prices creates an opportunity for manipulation.

Modern measurement tools have largely solved these problems, but they focus on big data and market prices, which creates problems with recalculation. The nominal value added has to be additionally calculated. That said, any estimates in industry sectors are more accurate than in services because market prices are unknown and the estimates are controversial. Therefore, data for coal and oil work better. The more complex the product, the worse it is reflected by the measurement tools.

Accounting for military expenditures and defence production and their impact on economic growth also pose significant problems. Alexey Ponomarenko, an economist and statistician who worked at Goskomstat (the Soviet predecessor of Rosstat, Russia’s Federal State Statistics Service) in the late 1980s and 1990s, studied these issues and solved the methodological problems of including military expenditures and military production in the system of national accounts. He described an estimate system based on partially published data.

However, in the Soviet economy, it is often difficult to separate military from non-military expenditures, particularly when it comes to the mobilisation of resources of the national economy to solve defence problems

There is still the question of how much the statistics allow us to observe the informal economy—the black market, underground industries, and a variety of ‘pushers’ (sellers, promoters) and intermediaries in informal barter deals — which according to various data amounted to about 12-12.5% of the economy. In the works of Alexey Ponomarenko the informal economy appears in the balance sheet of the national economy in the value of agricultural products and construction materials. If these data are taken into account, Ilya Voskoboynikov believes, the growth rates of the Soviet economy as a whole and the economy of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic may decrease.

In general, the Soviet GDP needs to be recalculated. Now economists and historians have more historical statistics, which were previously secret. In addition, data on the informal sector is now available, which may be very surprising.

The HSE researcher believes that the problem of recalculating economic growth of the 1930s will be the most difficult, because data from these years is more sketchy, and methods for calculating the gross national product were still under development. In the 1950s, methods had improved and intersectoral balances were introduced. Then the balances of the Soviet member states began to be developed and they began to participate more actively in the development of statistics.

According to Ilya Voskoboynikov, the impact of political repression on the economy and its growth in the USSR is also difficult to measure. He believes that the decline in labour supply weakened labour motivation and that working in a labour camp environment changed labour relations and reduced the efficiency of the economy.

At present, there are By 1960 the Soviet economy was about half the size of the American economy. Until the mid-1970s, the Soviet economy grew at a faster rate than the U.S. economy. Then it slowed.no scientific works that facilitate a full comparison of production, labour productivity, and their growth rates between the USSR and the leading capitalist countries for the entire period. Ilya Voskoboynikov noted that the growth rates of the USSR and U.S. economies were generally comparable, but they differed significantly in different periods. In particular, they were very high during the NEP (New Economic Policy) and period of industrialisation: the Soviet Union managed to narrow the gap with the United States during the Great Depression of 1929-1933, but the national economy was subjected to heavy destruction during World War II.

By 1960 the Soviet economy was about half the size of the American economy. Until the mid-1970s, the Soviet economy grew at a faster rate than the U.S. economy. Then it slowed

Ilya Voskoboynikov concluded that he could not predict what the results of recalculating data on production in the Soviet economy and its growth would be. ‘We are [like the proverbial soldier] trying to make soup out of a hatchet and get ingredients that we can actually eat. We all understand: the existing numbers are not good enough for us, but the approach from different sides of the economy is complicated. It will take a lot of data and time,’ he said.

Professor Oleg Budnitskii, Director of the HSE University International Centre for the History and Sociology of World War II and Its Consequences, described his impressions of his recent work: ‘I had no idea of the scale of railway theft during the war. People were amazingly resourceful, stealing extreme amounts during the war and after. I don't know how it can be counted economically, but the scale was impressive,’ he concluded.

The moderator of the seminar, Professor Oleg Khlevniuk, Chief Research Fellow of the Centre, noted that scientists should hardly expect quick results in the recalculation—it is not only about market and non-market prices, but also about the fundamental difference between the two systems. He stressed that historians need to continue cooperating with economists in the study of modern history.

- About

- About

- Key Figures & Facts

- Faculties & Departments

- International Partnerships

- Faculty & Staff

- HSE Buildings

- Public Enquiries

- Studies

- Admissions

- Programme Catalogue

- Undergraduate

- Graduate

- Exchange Programmes

- Summer University

- Summer Schools

- Semester in Moscow

- Business Internship

-

https://elearning.hse.ru/en/mooc/

Massive Open Online Courses

-

https://www.hse.ru/en/visual/

HSE Site for the Visually Impaired

-

http://5top100.com/

Russian Academic Excellence Project 5-100

- © HSE University 1993–2024 Contacts Copyright Privacy Policy Site Map

- Edit